Developing a turn based real-time battle game with Next.js and WebSockets

March 31, 2022

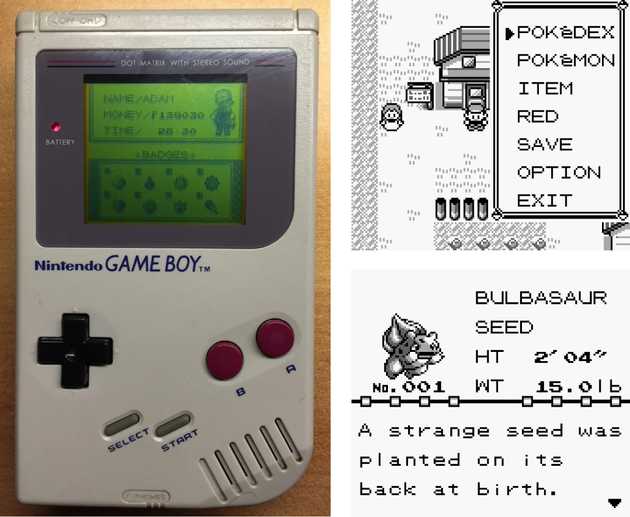

One thing on my side project bucket list for a number of years is a simple implementation of the battle system in the original Pokemon Red/Blue games on the Game Boy, for use by two users over the web using real-time web technologies. These games were a big deal for me in the late 90’s, having fond memories of being literally obsessed with the thought of spending hours exploring the world and catching Pokemon. Even on the small 4.7x4.3cm, 160x144px screen, the experience was magical.

I’ve spent a little time developing this battle system using JavaScript based web tech so In this post I’ll document some of the challenges faced, and the approaches used.

The game can be found here.

Just a side note to mention that I am in no way affiliated with Pokemon or Game Boy. This project is intended as a development learning exercise.

Overview of the game

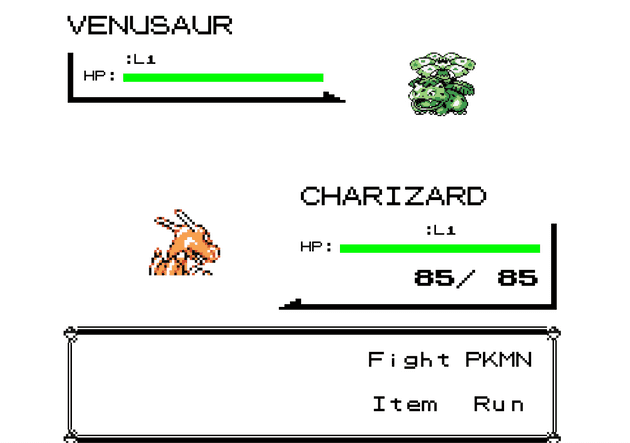

The effort involved in creating an entire Pokemon game is colossal, and also not what I was interested in replicating. My interests were solely on recreating the turn-based battle system. For those who can’t remember or was not fortunate enough to witness magic like this, here’s what the actual Game Boy game looked like:

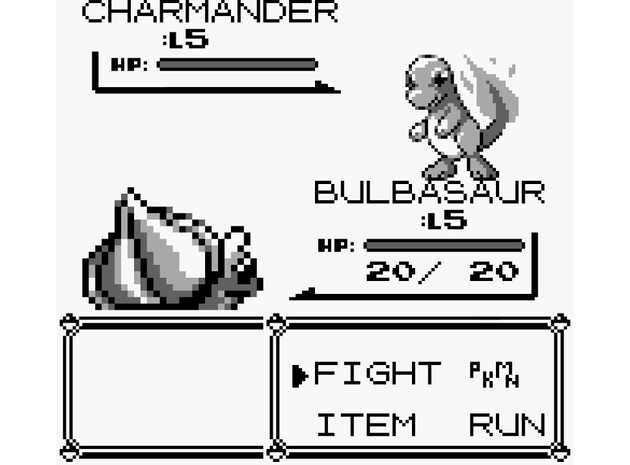

A lot of the original game involved exploring the world, talking to people, and picking up items, but one big part of the game is the battle system:

In order to recreate the battle system, there’s a few things that need to be addressed and implemented:

- Users need to be able to start a new battle, or join another user to begin a battle

- Users need to be able to select a Pokemon each

- Users need to be able to select attacks for their Pokemon to perform, in a turn-based system

- The system needs to determine the stats for each Pokemon, including damage inflicted on the opponent, and XP gained to the winning Pokemon at the end of the battle

- The system needs to log each user’s Pokemon XP, and allow a user’s Pokemon to level up, leading to the Pokemon becoming more powerful

- User’s pokemon need to be able to learn new attacks when levelling up

The tech stack for developing the game

The idea of this exercise is to make the simplest possible implementation of the Pokemon battle system, in the shortest time, just to tick it off my bucket list. With that in mind, I went for technologies which are quick to get up and running:

- Next.js was used because of the simple architecture and hosting. Having an SSR application was important as I wanted the server and client code to sit nicely together in the same code base, whilst having the performance benefit of server side processing of data.

- React.js was used from a crucial need to rely on application state - a core aspect of every game, regardless of size.

- Tailwind CSS was used as a quick way to add styling, with simple, lightweight styling being key for such a stripped back game in terms of UI.

- WebSockets was used to have the best, real-time user experience when using the battle system, including attacking, and selecting characters.

- Postgres was used to hold data about the user IDs, battles, and XP gained for each users Pokemon.

Challenges

There were many challenges to overcome when building a game even as simple as this one - too many to go into detail here. Instead, I’ve picked out a few of the more interesting ones which will hopefully help anyone looking to do something similar.

Getting Pokemon data, including images from front and back of Pokemon

A lot of data is needed for the game, and there are a lot of sites out there which hold all different sorts of data. For example, we need images of each Pokemon, on a transparent background, of both the front and the back of the Pokemon (the back being the current player, and the front image showing the opponent player). We also need each Pokemon’s battle stats such as HP, Attack Power, Defense, Speed etc.

I originally looked at using pkmn.net to obtain images, but after a couple of hours of extracting a small set of images and manually processing them to remove background colour and increase the quality, it was going to take way too long so I looked for another approach.

Similarly, another great website called pokemondb.net was originally used to provide Pokemon battle stats. Playing the game 20 something years ago, I wasn’t considering all the stats in the scope needed here, so I had to do a lot of research into how the stats were actually used and what data was needed. Although pokemondb.net was great for research purposes, it was still a huge undertaking to grab all the stats in the right format for how I’d use it in the app.

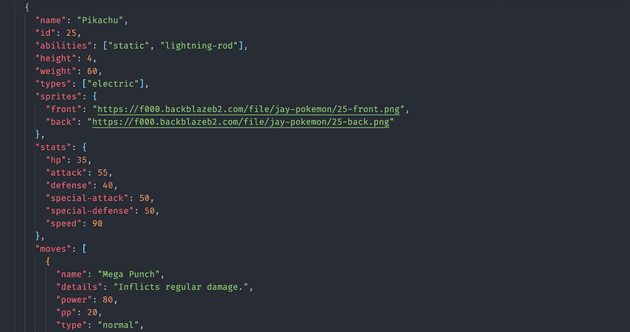

That’s when I came across PokeAPI.co - a free to use, uncapped API for anyone to obtain any data you can think of about Pokemon. After doing the research before to determine what I needed, this API provided everything in an easily accessible medium.

I could have just used PokeAPI directly during a battle - i.e. send API calls to get a specific Pokemon’s stats before a battle, but instead I wanted to get the needed data from the API and store it locally on my servers. This was important to me so the app would stay performant and not rely on a third party service. With this in mind, I decided to write a script to pull in the needed data from PokeAPI ahead of time, and store the data in a JSON file on my server:

;(async function () {

const response = await fetch(process.env.POKEMON_API_URL)

const pokemons = await response.json()

const finalArray = await Promise.map(

pokemons.results,

async function (pokemon) {

const response = await fetch(pokemon.url)

const data = await response.json()

// Get images from PokeAPI, increase size by 3x, and upload to object storage on Backblaze

let imageUrls = []

try {

imageUrls = await uploadToB2({

imageUrlArray: [

data.sprites.versions["generation-i"]["red-blue"][

"front_transparent"

],

data.sprites.versions["generation-i"]["red-blue"][

"back_transparent"

],

],

pokemonId: data.id,

})

} catch (e) {}

return {

name: pokemon.name.charAt(0).toUpperCase() + pokemon.name.slice(1),

id: data.id,

abilities: data.abilities.map((a) => a.ability.name),

height: data.height,

weight: data.weight,

types: data.types.map((t) => t.type.name),

sprites: {

front: imageUrls.length ? imageUrls[0] : "",

back: imageUrls.length ? imageUrls[1] : "",

},

stats: data.stats.reduce((result, item) => {

const stat = item.base_stat

const name = item.stat.name

return { ...result, [name]: stat }

}, {}),

// Traverse the API to get only the needed data for moves

moves: await Promise.all(

data.moves

.filter((m) => {

return (

m.version_group_details.filter(

(d) => d.version_group.name === "red-blue"

).length > 0

)

})

.map(async (m) => {

const response = await fetch(m.move.url)

// Also contains data on other pokemon with same move

const move = await response.json()

const learnedDetails = m.version_group_details.filter(

(d) => d.version_group.name === "red-blue"

)[0]

return {

name: move.names

.filter((n) => n.language.name === "en")

.map((n) => n.name)[0],

details: move.effect_entries.length

? move.effect_entries[0].effect

: null,

power: move.power,

pp: move.pp,

type: move.type.name,

accuracy: move.accuracy,

learnedDetails: {

level_learned_at: learnedDetails.level_learned_at,

move_learn_method: learnedDetails.move_learn_method.name,

},

target: move.target.name, // some moves target the opponents and some target user - we want to target only opponents

}

})

),

}

},

{ concurrency: 5 }

)

// Write ALL data for Pokemon Red/Blue, including moves, battle stats, etc.

fs.writeFile(

"../pages/data/pokemon-all.json",

JSON.stringify(finalArray),

(err) => {

if (err) {

throw err

}

console.log("JSON data is saved.")

}

)

const basicData = finalArray.map((f) => {

return {

id: f.id,

name: f.name,

types: f.types,

stats: f.stats,

sprites: f.sprites,

}

})

// Write a separate file for basic data on Pokemon, used for character selection screen

fs.writeFile(

"../pages/data/pokemon-basic.json",

JSON.stringify(basicData),

(err) => {

if (err) {

throw err

}

console.log("JSON data is saved.")

}

)

})()Starting from the top - the uploadToB2 function is used to get the front and back images of each Pokemon from the API, and upload to my own object storage on Backblaze. On first attempt, I noticed the image quality was very poor when added to my web app, because the images from the API are only 40px square. When placed in the web app and enlarged to a 200px square, the image was stretched and looked terrible. To combat this, I use sharp to resize the images properly before uploading to storage. The images are resized to 400px square, whilst still preserving the raw, pixel quality almost perfectly:

The

uploadToB2function was detailed in a post from last month.

Then the rest of the relevant data is pulled in, such as name, abilities, height, weight, etc. including the battle moves. As the API is structured in such a way that requires links to be followed on each API node (because there’s so much data in the API), I am chosing to only pull in a small set of data required for my app by traversing the API links, and this is mainly seen in the moves map.

The API has no limit in terms of usage, as explained on the PokeAPI homepage, but there’s still throttling involved to stop repetative, programmatic abuse of the API. This caused my script to fail after getting to around the 30th Pokemon. To get around this, I used Bluebird concurrency so only 5 Pokemon requests are in action at any one time.

Finally, all data obtained at the end of the script is saved to two files:

- pokemon-all.json

- pokemon-basic.json

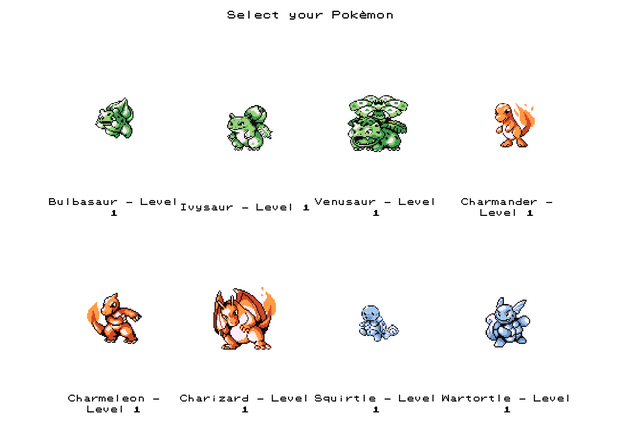

These two files are needed because the pokemon-all.json file is 2.1MB which is too big for me to bring back to the front end on the character selection screen:

This character selection screen only needs the front image, and Pokemon name which for each of the 150 Pokemon in the pokemon-basic.json file totals only 56KB.

Ending the game when one user refreshes the screen

The key when making a real-time web app involving multiple users is to ensure state between all users is up-to-date and in sync. This can be difficult depending on the app as users might be on different screens or different parts of the app. As I wanted to keep my web app as simple as possible, I didn’t spend loads of time reading a production level solution.

For example, consider the battle screen with two users sharing state:

During the battle, no state is being stored in a database. Data is saved at the very end of the battle, but until then, all state exists on the local machines of the two users. If one user decides to refresh their browser, this would cause state to be reset, including HP, damage, action points, etc.

Traditionally, and in a proper, production application, state would be stored on a remote system (if only for a temporary time), and hydrated on page refresh. Or perhaps stored on the device, and hydrated on page refresh. As I didn’t want to delve that far in to the development, I instead decided to develop the app to end the game for both users if one of the users refreshes their browser.

My first attempt at ending the game on browser refresh involved hijacking the page refresh using an approach outlined in this SO post. I couldn’t get this to work nicely with Next.js, as I couldn’t get the system to distinguish between a genuine page refresh and a Next.js router.push().

The final and working attempt included using cookies to store data to determine if the page was refreshed. Specifically, when the characters are selected, but before the page battle screen is shown, a cookie is saved for scriptemonFirstBattleEntry:

Cookies.set("scriptemonFirstBattleEntry", true, {

expires: 1,

})

router.push("/battle")Then on the battle screen, when the match is ready and all pre-battle state processing is done, the previously set cookie is searched for:

useEffect(() => {

// Run once when match is set up (i.e. character array has been sorted and first player selected)

if (matchReady && firstPlayerName) {

const isFirstBattleEntry = Cookies.get("scriptemonFirstBattleEntry")

if (isFirstBattleEntry) {

setIsCurrentTurn(userSelection.thisUser.characterName === firstPlayerName)

Cookies.remove("scriptemonFirstBattleEntry")

} else {

// User has refreshed the page so should cancel the match for both users

setTimeout(() => {

return pushMessage({

action: "matchRefreshed",

userId,

matchId,

})

}, 300)

}

}

}, [matchReady, firstPlayerName])If it’s the first time the user is on the battle screen, this cookie will exist because it’s just been set. However when the match starts and the first user’s turn is initiated, the cookie is removed, so subsequent checks on this cookie (i.e. on page refresh) will show that the cookie is no longer present.

If the system determines that the page has been refreshed, a WebSocket message is broadcasted to both users with a matchRefreshed action, which is listened for, and set to end the game when received:

const listenForMatchRefresh = () => {

let channel = initSocket(matchId)

channel.bind("matchRefreshed", function () {

return setEndGame({

loser: false,

areYouWinner: false,

levels: null,

})

})

}Calculating XP and damage

The final puzzle which needed unravelling was to calculate the battle stats for damage inflicted to the opponent, and also XP gained when winning a battle.

I only found one source of information for this, which was the excellently documented bulbapedia website, and it covers pretty much every aspect of all Pokemon games.

The Damage Calculation section of the above page explains how to calculate the damage inflicted on the opponent. This calculation requires all the stats I mentioned earlier in the post which have been retrieved from the PokeAPI previously, such as Power, Attack, Defense etc.:

One critical part of this calculation is the Pokemon “level”, which starts off as 1 in the game, and increases in proportion to the amount of XP that is gained at the end of each battle. The higher the Pokemon level, the more powerful damage can be inflicted.

Similar to the calculation for Damage, the Bulbapedia website also details how to work out the XP given at the end of a battle.

As you can see from both of these links, the proper games are very complex in terms of the nuances between different generations of the game. Pokemon Blue and Red seem to be the simplest implementations compared to new games like Pokemon Go, but I’ve still not even scratched the surface in the real calculations which are used in the first generation games. For example, here’s my calculation for the XP:

export function calcXp({ player }) {

const isTrainer = 1.5

const yields = Math.max(...Object.entries(player.stats).map((v, i) => v[1]))

const luckyEgg = 1

const levelOfVictorious = 1

const pointPower = 1

const numberOfParticipants = 1

const originalTrainer = 1

const shouldEvolve = 1

const xp =

(isTrainer *

yields *

luckyEgg *

levelOfVictorious *

pointPower *

originalTrainer *

shouldEvolve) /

(7 * numberOfParticipants)

return xp

}The only real used data to determine the final XP number here is the player.stats information. Everything else I’ve just set to “1” or “1.5” as a flat number as it’s either too complex or irrelevant to adjust for the purposes of this development project.

Having said that, the XP is suitable in my app, due to the legitimacy of the player.stats data:

Thanks for reading

If you missed the links to the live project:

The game can be found here.

Senior Engineer at Haven